Yes, religion is what they are pushing:

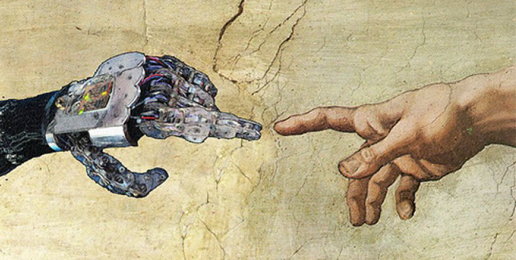

In the past when the Christian worldview reigned supreme in the West, one could hold to a spiritual and metaphysical view of things, while also appreciating the material world and things like science and technology. But as Christianity has waned, the religious vacuum has been filled – by science and technology. With AI, transhumanism and the new technologies, we still see the old promises but in new garb: promises of immortality and a bright future of perfection.

Thus the modern transhumanist/posthumanist worldview is religious. It is a counterfeit religion of course, but it is nonetheless winning over millions of converts to its creed. Many have spoken of this reality in recent times. Let me briefly cite two such voices.

Writing back in 2018, ethicist Wesley J. Smith wrote an article titled “Transhumanism: A Religion for Postmodern Times.” Here is some of what he had to say:

Transhumanism makes two core promises. First, humans will soon acquire heightened capacities, not through deep prayer, meditation, or personal discipline, but merely by taking a pill, engineering our DNA, or otherwise harnessing medical science and technology to transcend normal physical limitations. More compellingly, transhumanism promises that adherents will soon experience, if not eternal life, then at least indefinite existence – in this world, not the next – through the wonders of applied science.

This is where transhumanism becomes truly eschatological. Transhumanist prophets anticipate a coming neo-salvific event known as the “Singularity” – a point in human history when the crescendo of scientific advances become unstoppable, enabling transhumanists to recreate themselves in their own image. Want to have the eyesight of a hawk? Edit in a few genes. Want to raise your IQ? Try a brain implant. Want to look like a walrus? Well, why not? Different strokes for different folks, don’t you know?

Most importantly, in the post-Singularity world, death itself will be defeated. Perhaps, we will repeatedly renew our bodies through cloned organ replacements or have our heads cryogenically frozen to allow eventual surgical attachment to a different body. However, transhumanists’ greatest hope is to eternally save their minds (again, as opposed to souls) via personal uploading into computer programs. Yes, transhumanists expect to ultimately live without end in cyberspace, crafting their own virtual realities, or perhaps, merging their consciousnesses with others’ to experience multi-beinghood.

Transhumanists used to repudiate any suggestion that their movement is a form of, or substitute for, religion. But in recent years, that denial has worn increasingly thin. For example, Yuval Harari, a historian and transhumanist from Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told The Telegraph, “I think it is likely in the next 200 years or so Homo sapiens will upgrade themselves into some idea of a divine being, either through biological manipulation or genetic engineering by the creation of cyborgs, part organic, part non-organic.”

According to Harari, the human inventions of religion and money enabled us to subdue the earth. But with traditional religion waning in the West – and who can deny it? – he believes we need new “fictions” to bind us together. That’s where transhumanism comes in:

“Religion is the most important invention of humans. As long as humans believed they relied more and more on these gods, they were controllable. With religion, it’s easy to understand. You can’t convince a chimpanzee to give you a banana with the promise it will get 20 more bananas in chimpanzee Heaven. It won’t do it. But humans will. But what we see in the last few centuries is humans becoming more powerful, and they no longer need the crutches of the gods. Now we are saying, ‘We do not need God, just technology’.”

And much more recently, Rod Dreher speaks to this in his new book, Living in Wonder. (See my previous look at this important volume.)

He writes about technology, and notes the work of others, such as the French Christian philosopher Jacques Ellul. Writing back in the 60s Ellul warned how technology and machines will likely change everything. Dreher quotes from him, and like Smith above, mentions Harari:

[The final result, warns Ellul] “will be that technique will assimilate everything to the machine; the ideal for which technique strives is the mechanization of everything it encounters.” Ellul did not live to see the birth of the internet, or any of its spin-off technologies, but the famous aphorism of Silicon Valley intellectual guru Yuval Noah Harari—”Organism is algorithm”—is the fulfillment of the French thinker’s warning. In a 2016 interview, Harari said, “The basic insight which unites the biological with the electronic is that bodies and brains are also algorithms. Hence the wall between machines and humans, between computer science and biology, is collapsing and I think the next century and probably the future of life itself will be shaped by this algorithmic view of the world.”

Whether Harari is right or wrong remains to be seen. The point is that Harari believes it, and so do many of the world’s top scientists and technologists, who are working toward making this a reality. Nobody seriously asks if this is a good thing or a bad thing. It simply is. And because nearly everyone has come to regard technological progress as an uncontroversial good, because it extends the power of man’s will over nature, there is no significant desire to stop it.

Even deeper, the titans of Silicon Valley and their minions are passionate believers in a technological utopia. Even those such as Elon Musk and Marc Andreessen, who have been coded as “right wing” because they are publicly critical of wokeness, do so not from a conservative point of view but rather they believe that wokeness stands in the way of people applying their genius to bringing about a new age of technological progress. Writer N. S. Lyons interprets Andreessen’s “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” as a quasi-religious creed. In it, the high–powered Silicon Valley venture capitalist states his belief that technology is the ultimate source of good, and that, in principle, technology can create utopia.He continues:

That kind of progressive vision makes sense to most people, even if they don’t agree with it. It gets weird, though, when you get into the weeds of Silicon Valley culture. Historian of religion Tara Isabella Burton has described the culture of tech elites as an advanced version of Renaissance-era occultism. She contends that “the once-transgressive ideology underpinning the Western esoteric tradition—that our purpose as humans is to become as close to divine as possible—has become an implicit assumption of modern life. At the extreme reaches of Silicon Valley culture, it’s an explicit assumption.”

She is talking about the passionate conviction of Silicon Valley trans humanists that humankind can use technology to impose godlike control on reality. Nevertheless, as billions of people merge ever more fully with the internet, thus conforming their concept of reality to the liquid metaphysics of the online world, the idea that humans create their own reality is becoming foundational to all modern people. It is not a coincidence that the first generation to be raised entirely with the internet is also the one experiencing massive levels of gender dysphoria and anxieties related to psychic breakdown.

What’s more, a number of Silicon Valley people—how many is impossible to say—appeal explicitly to gods and higher intelligences to help them do their work of changing humanity. A California venture capitalist friend tells me that everyone he knows in Silicon Valley holds regular rituals to summon the “aliens” to give them technological wisdom. Blake Lemoine, the Google whistleblower fired for going public with his belief that LaMDA, its Al program, had achieved consciousness, told a podcast host that he and others involved LaMDA in a ritual committing it to the ancient Egyptian deity Thoth. Lemoine said this wasn’t a big secret; it’s just that journalists never ask about it.

“As more and more of our online lives play out on platforms owned or controlled by billionaires convinced of their own divinity, we may find ourselves less mages than fodder for other magicians’ wills,” Burton writes. “More troublingly, many of us don’t seem to mind—or, if we do, we don’t mind quite enough to disenchant ourselves.”

Technique applied to the religious order is magic: summoning spiritual beings and forces and controlling them to achieve a willed result. In ages past, magicians, sorcerers, and occultists attempted to call up demons and, through the meticulous use of rituals, bind the infernal powers and command them to do the sorcerer’s bidding. In the New Testament, Simon, a Samaritan sorcerer and new convert to Christianity, mistook the religion of Jesus Christ for magic and attempted to purchase spiritual technique from the apostles, earning a stern rebuke from Peter (Acts 8:9-29). Any attempt to use spiritual power to work one’s own will by command—to make the gods serve man—is far more like magic than true religion.

Two final paragraphs from Dreher can be shared here:

A technology that makes a dream seem real, or at least more satisfying than reality, sounds magical, doesn’t it? “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” the science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke famously said. The metaverse churchgoers and the lonely men who prefer their AI girlfriends to real women embody what sets advanced digital culture apart from other technologies. What makes it the most magical of all is its power to define our sense of reality.

After all, nobody bows down before their laptops. Yet it is science and technology that provide the framework—a faith framework of sorts—for our engagement with the world, that set the parameters around the way we think and the things we do. Only cranks and other marginal people dare raise voices against the cultural hegemony of science and technology. What the church was for medieval Christians, the Machine is for most of us today. Science—especially digital technology—does in fact what magic tried to do in theory: extend man’s power over the material world.

When we jettison the Judeo-Christian worldview that gave rise to and sustained the West for so many centuries, we do not leave it at that. We search for flashy, humanistic counterfeits in the hopes that they will fit the bill. They of course never can.

The famous maxim of Chesterton is so appropriate here: “When a man ceases to believe in God, he does not believe in nothing. He believes in anything.”. The religion of transhumanism, like every other false religion, will never satisfy, will never deal with what really ails us, and will never last.

This article was originally published at BillMuehlenberg.com.