Have you ever wondered why, in the freest, most prosperous, most economically booming country in the world—the United States—1 in 8 people receive food stamps due to poverty, while we still report that 1 in 7 people face chronic food insecurity?

I wonder. I wonder how this could be true.

I started looking into this when I found that food banks in our area, many of them housed in churches, began providing largely anonymous delivery services to people who supposedly need food but are afraid to visit the food bank facilities for fear of being discovered by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. Reportedly, they are afraid they will be met at the local food pantry by federal agents, arrested, and deported.

I started looking into this when I found that food banks in our area, many of them housed in churches, began providing largely anonymous delivery services to people who supposedly need food but are afraid to visit the food bank facilities for fear of being discovered by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents. Reportedly, they are afraid they will be met at the local food pantry by federal agents, arrested, and deported.

So what’s happening is that the food banks—which are substantially funded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)—are trying to make it easier for illegal aliens to evade capture and deportation by Homeland Security. Ultimately, one federal agency is effectively undermining another’s mission.

These contradictions pushed me to look deeper into how our hunger relief system really operates. How big is the hunger problem in America? Who controls the system? And why would those running the show attach themselves to the ICE resistance movement?

My attempt to answer these questions led me to discoveries I didn’t expect: a vast, opaque system built on subjective measurements, corporate tax incentives, and federal monopolies—all operating with little oversight despite being funded with billions in taxpayer dollars. The more I investigated, the more the numbers stopped adding up. The stories didn’t match reality. And the people running this system are getting very, very rich.

Trying to investigate the food bank system is like auditing a ghost. These organizations operate under 501(c)(3) nonprofit status, which shields them from most state regulation. They receive billions in federal commodities through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and state grants, yet their allocation decisions are made behind closed doors in meetings that aren’t public.

The system is deliberately opaque. Food banks report to the IRS using Form 990, but those filings don’t reveal allocation formulas, they don’t publish board meeting minutes, and they don’t provide details on travel and meeting expenses. They also don’t publish conference transcripts or list salaries for individual employees, except for officers.

Additionally, they don’t show whether federal demographic formulas are actually followed. They are entirely exempt from any Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, even though they are nearly entirely funded by federal subsidies and corporate donations driven by increased tax write-offs.

States designate food banks as TEFAP distributors through contracts that are not easily accessible to public scrutiny. The entire system operates in a regulatory gray area: too nonprofit to be regulated like a business, too government-affiliated to be pure charity, too politically connected to face serious oversight.

This opacity isn’t accidental. It’s structural and protects a system that has grown into a $4.9 billion industry based on a ‘hunger’ measurement that might not accurately reflect reality.

For nearly 30 years, the United States has relied on a single annual survey to assess “food insecurity” by asking households about their anxiety, worry, and perceptions of food access over the past year. This method forms the foundation of the $4.9 billion charitable food industry. Still, it does not measure hunger or actual food deprivation—only self-reported emotional states that are entirely subjective and unverified.

The Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS), conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau and sponsored by the USDA, asks households 10-18 questions about their feelings and experiences related to food. A household is classified as food insecure based on just three affirmative responses to questions such as:

“Were you worried whether food would run out before getting money to buy more?” (measuring anxiety, not actual shortage)

“Could you afford to eat balanced meals?” (measuring subjective perception of affordability, not actual nutrition)

“Did you cut meal size or skip meals?” (behavioral claim, unverified and subject to 12-month recall bias)

There is no objective standard for defining a “balanced meal,” no nutritional assessment, no caloric measurement, and no medical verification. A household reporting that they “sometimes worried” food would run out is classified the same as one where adults regularly skip meals. Both are labeled “food insecure.”

The 2006 National Academies Panel that reviewed this measure concluded: “The survey does not directly measure the physiological condition of hunger” and recommended that USDA stop using the word “hunger” entirely—a recommendation ignored by the food industry that still uses “hunger” in marketing materials 19 years later.

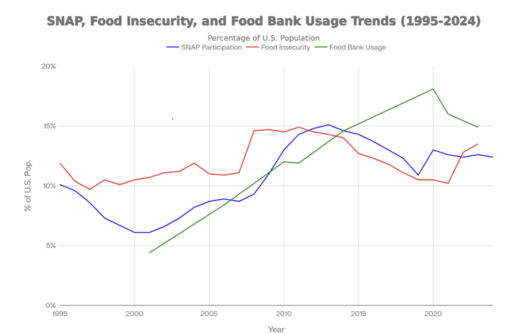

If food insecurity measurement were meaningful, we would expect increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation and expanded food bank distributions to decrease food insecurity rates. Instead, all three numbers move together, rising and falling with economic conditions rather than showing inverse patterns.

2001-2010: SNAP doubled from 6.1% to 13.0%; food insecurity surged from 10.7% to 14.5%; food bank usage tripled from 4.4% to 12.0%

2010-2019: All three declined together as the economy recovered

2023: Food bank usage (14.9%) exceeds food insecurity (13.5%)—mathematically impossible if these systems served only the food insecure

The correlation is clear: +0.593 between SNAP and food insecurity, +0.815 between SNAP and food bank usage. These are not inverse relationships that would show “solutions.” They are responses to the same underlying poverty, and the system has no incentive to eradicate poverty, only to manage it profitably.

Feeding America’s national leadership earns $7 million annually in compensation. Regional food bank leaders make between $250,000 and $500,000. Marketing vendors take in $37.6 million each year to persuade donors that hunger is getting worse, using carefully crafted stories about “worried families”—technically false and emotionally compelling claims.

The food insecurity measurement provides a perfect cover. It is subjective enough that it can’t be proven false, broad enough (50 million Americans now classified as food insecure) to support ongoing growth, and essentially unaffected by whether real hunger is addressed.

Food insecurity, as measured, is not a reliable, objective way to assess actual hunger. It is a subjective collection of self-reported feelings, perceptions, and recalled behaviors—none of which are verified —and all of which may encourage exaggeration. After 30 years of measurement, $4.9 billion spent annually, and a network of 60,000 food banks, food insecurity remains worse than when measurement began.

An objective person must conclude that claims of increasing food insecurity are false — not because they are factually incorrect, but because of their misleading purpose. They are intentional justifications designed to benefit a self-sustaining industry that profits from perpetuating hunger rather than eliminating it.

The modern food pantry movement didn’t originate from a planned, evidence-based response to hunger. Instead, it emerged as a spontaneous reaction to economic shocks in the 1970s and 1980s, then grew into a lasting, parallel food system that now helps tens of millions of people each year—without significantly reducing food insecurity.

The earliest food pantries in the United States were simple “emergency cupboards” run by churches and community groups during the economic turmoil of the 1970s. They were local, volunteer-driven, and explicitly temporary—meant to help a family through a job loss or crisis. Around the same time, the first food banks appeared as warehouse-style intermediaries that could collect surplus food from manufacturers and wholesalers and distribute it to those small pantries and soup kitchens.

In 1979, these regional food banks formed a loose national alliance called Second Harvest, which was later rebranded as Feeding America.

The infrastructure started with President Reagan’s 1981 executive order that distributed surplus government cheese. The Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) formalized this in 1983, designating states to contract with “eligible recipient agencies”—food banks, churches, community groups—to distribute USDA commodities to those in need.

At this stage, food banks were only one distribution channel among many. But Reagan-era social welfare cuts created surging demand for emergency food assistance, and food banks positioned themselves as the professional solution: they had warehouses, logistics networks, and volunteer infrastructure that churches and community organizations lacked.

When Reagan attempted to phase out TEFAP in 1988 as agricultural surpluses declined, the food bank lobby had become influential enough to prevent him. The Hunger Prevention Act of 1988 permanently authorized USDA food purchases for TEFAP and established a separate $40 million program specifically for “soup kitchens and food banks.” This marked the first time food banks were recognized as a distinct infrastructure in federal legislation.

Second Harvest—later renamed Feeding America—organized the lobbying campaign. They proved they could mobilize votes in Congress.

The 1990 Farm Bill, under President George H.W. Bush, made TEFAP permanent by removing the word “Temporary” from its name. This meant guaranteed infrastructure. States began consolidating their TEFAP contracts with Second Harvest food banks rather than managing numerous smaller distributors.

The main point was operational efficiency: Why work with 50 churches and community pantries when you could partner with a single regional food bank to manage downstream distribution? Food banks could receive truckloads of USDA commodities, store them in temperature-controlled warehouses, and then redistribute them to smaller “partner agencies.”

But efficiency came with a price: consolidation led to monopolization. By the early 1990s, churches and independent pantries that previously received TEFAP commodities directly from state agencies now had to go through Second Harvest food banks. The food banks had become gatekeepers.

President Clinton’s 1996 welfare reform—the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act—reduced federal benefits, leading millions to rely on food banks. TEFAP funding, which had been uncertain, was made mandatory again because Congress acknowledged that food banks had become the main safety net.

By 1996, the National Academy of Medicine later noted, Second Harvest “had secured contracts as the primary distributors of USDA TEFAP foods.” The transition was complete. What had been a diverse network of emergency food providers in 1983 was now a centralized system controlled by a single national organization and its state-level affiliates.

Here’s something most people don’t realize about “hunger relief:” large food corporations have been receiving payments—through significant tax write-offs—to donate surplus food inventory since 1976. Is this charity? Or subsidized waste management disguised as philanthropy?

When a food company has surplus inventory that won’t sell—damaged products, overstock, items nearing expiration—they face a choice:

Option 1: Throw it away. They write off the cost as a business loss. If they paid $100 for that inventory, they deduct $100. That’s it.

Option 2: Donate it to a food bank. Under tax code Section 170(e)(3), they can deduct not only their cost but also their cost plus half of the profit margin they would have earned if they had sold it.

Here’s the formula in plain English:

Cost: $100

What they would have sold it for (fair market value): $160

The “markup” or “gain”: $60

If they throw it away: $100 deduction

If they donate it: $100 + half of $60 = $130 deduction

That’s a 30% larger tax write-off for donating compared to discarding. In some cases, where markups are higher, the benefit can exceed 50%.

This isn’t an accident. Congress intentionally created this tax incentive in 1976 to encourage food donations. However, what it truly resulted in was a strong financial motivation for companies to build relationships with food banks — not because they care about hungry people, but because those relationships lead to larger tax deductions.

Before 1969, businesses could deduct the full fair market value of donated inventory, even when it greatly exceeded their cost. This was too generous and led to abuse, so Congress limited it in 1969 to allow deductions only equal to the cost.

Result? Food donations dropped sharply. It costs more to store and transport the products to the charity than to throw them away. Why would a company spend more on donating something when they get the same tax deduction by discarding it? Suddenly, “waste” became cheaper than “charity.”

To address this, Congress established the enhanced deduction formula (cost plus half the gain, capped at twice the cost), specifically for donations that help “the ill, needy, or infants.” The aim was noble: to encourage corporations to donate rather than discard.

What Congress received was a system where corporations could write off the same food at artificially inflated prices—prices that had nothing to do with actual food bank market prices or the real cost of providing food to hungry people.

The Obama administration established the legal framework for the monopoly. The 2008 Farm Bill raised TEFAP entitlement funding to $250 million each year, adjusted for inflation. More importantly, Congress repeatedly extended the enhanced food donation tax deduction through annual “extender” bills.

In 2015, Obama signed the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act, which made the enhanced deduction permanent and extended it to all types of businesses. The tax incentive that makes corporate donations to food banks 30-50% more valuable than discarding food is now permanent in the tax code.

This wasn’t coincidental timing. Douglas O’Brien—who would later become the Vice President of Programs at the Global FoodBanking Network—spent the Obama years at USDA. From 2009 to 2013, he served as Chief of Staff to Deputy Secretary Kathleen Merrigan at the Department of Agriculture under Secretary Tom Vilsack. In 2013-2014, he was Acting Under Secretary for Rural Development, overseeing a $30 billion portfolio. In 2015, he joined the White House Domestic Policy Council, where he led the White House Rural Council.

O’Brien was deeply involved in the USDA system during the renewal of TEFAP extenders, the expansion of food bank programs in the 2014 Farm Bill, and the enactment of the PATH Act, which made enhanced deductions permanent. He understood thoroughly how federal commodity programs worked with the Feeding America network.

Here’s why understanding the structure matters. There are actually two separate food streams in the hunger relief system.

Corporations can donate surplus food directly to any food bank, food pantry, or soup kitchen they choose. For example, your local grocery store donating day-old bread to your church’s food pantry is a direct corporate donation that qualifies for an increased tax deduction.

Feeding America doesn’t oversee these donations. Food banks—whether part of the Feeding America network or independent—all compete for these corporate partnerships. A local food manufacturer can choose to donate to a Feeding America food bank, an independent food bank, or directly to a small community pantry.

The tax incentive established the financial structure that made these donations attractive, but it did not establish a monopoly on corporate contributions.

The real control comes through The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), a federal program in which USDA purchases food from American farms and manufacturers and distributes it through state agencies to local food banks.

Here’s how the monopoly works:

The USDA spends billions of dollars on food each year through TEFAP. While the base appropriations range from $450 million to $470 million annually, supplemental purchases made through the Commodity Credit Corporation and other agricultural support programs have increased total TEFAP food expenditures to between $1.5 billion and $2.5 billion in recent years.

State agencies oversee distribution: Each state appoints a “State Distributing Agency” responsible for determining which food banks receive TEFAP commodities. In Illinois, that agency is the Department of Human Services (IDHS).

State agencies select “eligible local agencies.” In other words, states determine which food banks and emergency food providers are authorized to receive and distribute TEFAP food. In practice, this means states almost exclusively designate Feeding America network food banks as TEFAP distributors.

Feeding America captures 97% of TEFAP: About 97% of Feeding America’s partner food banks receive and distribute TEFAP foods. The network received over 1.5 billion pounds of TEFAP food in FY 2023-24—roughly one-quarter of all food distributed through its member food banks.

Feeding America itself describes TEFAP as “the backbone of the charitable food system.” Without federal TEFAP commodities, the entire food bank network would have considerably less food to distribute.

Independent food banks and small community pantries are mostly excluded from TEFAP distribution. If you’re not part of the Feeding America network, you probably can’t access federal commodities. You’re limited to competing for corporate donations and local fundraising.

This creates a two-tier system: Feeding America food banks receive federal commodities AND corporate donations, while independent food banks depend solely on private-sector contributions.

The result: Feeding America doesn’t dominate all food sources, but it does oversee the federal food pipeline that guarantees a steady, reliable, year-round supply.

The TEFAP monopoly becomes even more concerning when you think about how states allocate these federal commodities within their borders.

In Illinois, IDHS directly contracts with seven food banks to serve as TEFAP distributors statewide. The federal government requires TEFAP allocations to follow a specific formula (60% based on the poverty population, 40% based on the unemployment rate). However, there is limited oversight to ensure that states and coordinating organizations adhere to these formulas or that political factors do not influence the allocation process.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Feeding America and its member banks had fully adopted a corporate partnership model. The amount of food passing through the system surged—about 60 percent now comes from corporate and retail donors, with another quarter from USDA TEFAP purchases. Research indicates that roughly 60% of the food distributed by food banks falls into clearly unhealthy categories, such as sugary drinks, sweets, salty snacks, and highly processed foods. This is not a system built around nutrition; it is a system centered on moving surplus.

As the volume increased, so did the money—and the salaries. Feeding America now operates with hundreds of millions in annual revenue and maintains brand and compliance control over a network moving roughly 5 billion pounds of food each year. But the question nobody asks is: who is getting paid to manage this “charity”?

Feeding America National Office:

- CEO Claire Babineaux-Fontenot: $1.1 million per year

- 19 officers: All over $270,000 per year

- Remaining 386 employees: Average over $150,000 per year

- Total compensation for top leadership: Over $7 million annually

Greater Chicago Food Depository:

- CEO Kate Maehr: $475,000 per year

- 10 officers: All over $225,000 per year

- Remaining 357 employees: Average $70,000 per year

- Total compensation for top leadership: Over $3.4 million annually

To put this in perspective: as of 2023, the highest-paid government employee for the State of Illinois was a physician earning $382,500. Kate Maehr, running a “charity,” makes more than the state’s top doctor.

These salaries are just the beginning. Marketing budgets and vendor contracts cost tens of millions annually to produce emotionally charged messages about “hungry children” and “record food insecurity.” Feeding America paid marketing vendors $37.6 million in one year to maintain the narrative that hunger is worsening and that food banking is the crucial solution.

All of this rests on one crucial assumption: that hunger is worsening, food insecurity is at crisis levels, and the system needs constant expansion. But as we’ve seen, the data tells a different story—food insecurity rates haven’t improved despite 30 years and billions of dollars invested in this system. The industry needs the problem to continue because solving it would remove the justification for these budgets, salaries, and the entire structure.

While Feeding America solidified its domestic TEFAP monopoly, it quietly launched an international branch: the Global FoodBanking Network (GFN), founded in 2006 and based in Chicago. GFN’s early leadership included members from the nonprofit sector — among them Beth Saks, who had served as Feeding America’s CFO from 1994 to 1999 and became GFN’s CFO in 2008.

However, the organization’s character changed significantly in 2015 when Lisa Moon became President and CEO. Moon’s background was not in hunger relief; it was in national security. She had worked at the U.S. Department of Defense and the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), one of Washington’s leading defense and foreign policy think tanks, before shifting to “food security” at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. She is now a David Rockefeller Fellow of the Trilateral Commission, a high-level international relations group promoting cooperation among the U.S., Europe, and Japan.

When Douglas O’Brien left the Obama White House in 2017, he joined GFN as Vice President of Programs. His role: export the TEFAP model to more than 50 countries.

Under Moon and O’Brien, GFN grew from 20 to over 50 countries, reaching more than 40 million people. The corporate partners remain the same ones funding Feeding America: General Mills, Kellogg’s, PepsiCo, Cargill. The model is the same: positioning food banks as the professional infrastructure that connects corporate donors (seeking tax benefits) to governments (aiming to transfer hunger relief to NGOs) and to hungry people.

GFN hosts an annual Global Summit—formerly known as the Food Bank Leadership Institute—where 300-400 food bank CEOs from around the world learn “best practices.” These practices include board governance structures that enable recipient organizations to control allocation, government integration strategies that make food banks essential to TEFAP-style programs, and corporate partnership frameworks that generate tax-advantaged donations.

Target regions for expansion—Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, India—align perfectly with U.S. strategic interests in countering Chinese influence. Food banking isn’t just charity; it serves as a soft-power infrastructure that connects American multinationals to foreign governments through a network built initially with U.S. federal commodity programs.

What happened to the American food bank system between 1981 and 2015 was not the organic growth of community mutual aid. It was systematic federal integration with no public oversight or accountability:

1988: Federal legislation singles out food banks as a distinct infrastructure

1990: Program made permanent, favoring established organizations

1993-1996: States consolidate contracts, creating regional monopolies

2002: State associations formalize recipient control over allocation

2008: Farm Bill dramatically increases TEFAP funding

2015: PATH Act permanently locks in corporate tax incentives

2017: Obama USDA officials join GFN to export the model globally

The food bank monopoly was established through federal policy, backed by state contracts, and spread by former national security and USDA officials who fully understood what they had created: a privatized system for distributing government commodities and corporate surplus, controlled by politically connected nonprofit leaders with conflicting interests.

Historical data reveal a harsh truth: a larger charitable food system hasn’t reduced hunger. Instead, it has established a stable system where:

Corporations receive tax deductions and improve their reputation by donating products they were likely planning to discard anyway.

Large agribusiness suppliers benefit from guaranteed government purchase contracts through USDA programs that direct food to food banks.

Politicians create a dependable story, a photo backdrop to support increased spending, and patronage opportunities to reward supporters.

Feeding America and its affiliates gain funding, visibility, and policy influence by positioning themselves as the indispensable intermediary between “the generous” and “the hungry.”

Meanwhile, churches and individual donors are told that supporting this system is the best way to care for the poor.

The small, relational, community-based charity model that defined the earliest pantries has been replaced by a national logistics and branding operation.

The tax code and federal food programs didn’t cause hunger. However, they established the framework that enables political insiders to manipulate the system meant to resolve it. The real scandal isn’t the tax breaks or federal commodities. It’s what gets built on top of the system, who controls it, how much they are paid, all without public oversight, despite the whole system being funded by government money.

This hunger industrial complex was built from the top down. It’s intentionally opaque. It’s highly profitable for those who operate it. It measures success by subjective feelings rather than objective results. And it’s now gone global.

Looking back over the last 50 years, the pattern is clear. What began as emergency charity has evolved into an institutionalized, corporatized, and politicized system. Its scale is impressive, and its logistical capabilities are real. However, its track record of actually reducing the issues it aims to solve is dismal.

The growth of Feeding America and the food pantry movement does not indicate that we are finally ending hunger. Instead, it reveals that we have become used to managing poverty with surplus calories rather than addressing the underlying structural, political, and economic forces that cause it.

When food banks in my area started providing delivery services to help illegal aliens avoid ICE, I began asking questions. Those questions led me to uncover a system built on fraudulent measurements, corporate tax scams, federal monopolies, board conflicts of interest, and national security officials exporting American “solutions” worldwide.

Did we ever really have 1 in 7 Americans suffering from chronic food insecurity? I don’t believe so. But we definitely have a hunger industrial complex, which has become completely controlled by progressive political insiders, makes billions by claiming there’s a hunger crisis, and disguises itself as a charitable effort.

It’s far past time to remove government funding from the system, to get rid of the phony corporate giving that allows executives to posture as philanthropists, and bring the real charity work back to local churches.