If there’s one case from my years of criminal investigations that still stands out to me, it’s the story of Kenny Morrow. On paper, Kenny was everything a prosecutor despises — a convicted killer, a narcotics dealer, and a career criminal whose rap sheet dated back to the mid-1960s. But those records tell you nothing about the man he became or about how he almost single-handedly helped bring down one of the most violent street gangs in Chicago history — the El Rukns.

I first encountered Kenny’s name while heading an investigation into street gangs in Illinois. Most investigators build informants through leverage — you catch a man dirty, then offer him a deal. I wanted to try something different. I wanted someone who didn’t cooperate out of fear but out of conviction — a man who, despite his past, maybe because of it, might willingly put his life at risk to do the right thing. What I wanted was a true believer.

To find that man, I began by examining murder files. I looked for gang-related homicides that could reveal internal fractures and point me toward someone with both insight and motive to help pursue those responsible.

One case stood out — the murder of Henry “Mickey” Cogwell, a powerful South Side gang boss, gunned down in front of his home on Seeley Avenue in 1977. His name was already infamous. Cogwell had stood at the top of the “Main 21” of the Black P Stone Nation, and he was also the boss of Kenny Morrow’s brother, who was one of Cogwell’s bodyguards. After Cogwell’s murder, his bodyguard — Kenny’s brother — was also killed. Some long believed the killings to be part of Jeff Fort’s brutal consolidation of power as he reshaped the Black P Stone Nation into a new entity: the El Rukns.

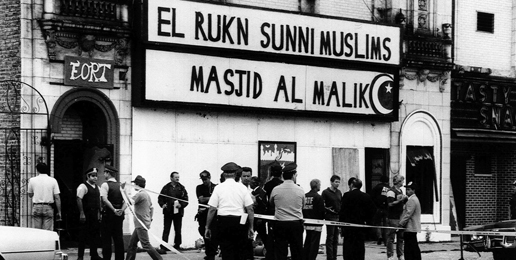

Fort turned the gang into a quasi-religious organization to give its “ministers” access to jails and prisons. Behind the robes and fezzes was a machine built on drugs, extortion, and intimidation. Later, Fort would become the first American gang leader convicted of conspiring with Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi to commit acts of terrorism inside the United States. But back in the mid-1970s, it was still just an extraordinarily well-organized, disciplined, and ruthless street gang.

I tracked Kenny through police records and then through his parents. To my surprise, they weren’t hardened street people at all. His mother was a schoolteacher. His father drove a CTA bus. They were churchgoing, middle-class folks who loved their son and prayed he’d find his way back to God. When I told them I believed he could use his past to make a big difference for the future of the whole community — that his knowledge and courage could bring down the very men who had destroyed his brother — they listened. I asked them to encourage Kenny to call me.

It took a month before that call came, and six months of slow, steady meetings before he trusted me enough to do more than listen. I didn’t offer him immunity or a reduced sentence. I offered him something else — a chance at reconciliation with his parents and absolution for his many crimes. I told him he could make his past serve the good, that he wasn’t too far gone for God to take him back. Even the worst of what he’d done could be turned into something that mattered. In time, he believed it.

Once Kenny agreed to work with me, he did it with the same intensity he had once devoted to the gang.

Back in the late 1960s, the gang world Kenny came out of was in flux. The old Blackstone Rangers had joined forces with roughly twenty other South Side gangs to form a single confederation called the Black P Stone Nation. Each of the twenty-one original gang leaders became part of what was known as the Main 21, the council that ruled the organization. At the top sat Henry “Mickey” Cogwell, formerly the leader of the Cobra Stones—one of the most violent groups on the streets. Cogwell’s rise also marked a turning point in what street gangs were willing to pursue. Under his leadership, crime expanded well beyond the usual gang activities. He learned to turn political connections into revenue, manipulating federal anti-poverty grants to funnel government money directly into the gang’s operations.

Cogwell also forged a working alliance with the Chicago Outfit. The mob saw profit in harnessing the muscle of Black street gangs, and Cogwell saw legitimacy in doing business with established racketeers. Kenny was deeply involved in that arrangement. One of his early assignments was to “persuade” African-American bar and restaurant owners on the South Side to buy exclusively from mob-connected suppliers. Most of them came around. Kenny was good at his job and sometimes had fun doing it.

One story he told me was about a bar owner who flatly refused to use the mob supplier. So the next night, a Saturday night, he walked into the bar with a box filled with a few dozen mice. He walked deep into the crowded bar, opened the box, and let the mice scatter. It caused pandemonium. The bar quickly emptied, and the next day the bar owner agreed to switch suppliers.

Because of Kenny’s history dating back to the Blackstone Rangers days and his very active involvement with the Black P Stone Nation, he already knew every major player. He could walk into rooms that only an insider could breach and come out with information no wiretap could ever produce.

One thing we learned from him was how deeply the El Rukns had embedded themselves in the machinery of government welfare. They became property owners and community activists while running scams that siphoned public money in every way possible. They’d buy deteriorating South Side buildings, rent them to their own members and to families on public assistance, and live off the state’s rent subsidies. Then they’d “sell” the same properties again and again, using straw buyers, each time inflating the price and collecting on fake insurance claims for the cost of reconstruction and lost income when they torched the buildings.

One property became a grotesque welfare pipeline. The gang housed prostitutes there, who turned over part of their earnings to the El Rukns and collected welfare benefits as well. They even opened a state-subsidized day-care center in the same building — a place for the children so the mothers could keep working the streets. The gang took its cut of those payments, too. Every dollar intended for the vulnerable passed through the hands of predators. If there were ever a clearer example of bureaucratic blindness — whether through ineptitude or corruption — I never saw it.

When I left state service in late 1983 to start my own investigative agency, I turned Kenny over to the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force. Federal agents acted quickly on the information Kenny had already provided. Kenny’s access and credibility made him indispensable to the Task Force. Within months, the information he gathered led to secret indictments of two of Fort’s generals. They were arrested, flipped, and released in one night, then set loose without anyone knowing of their criminal problems.

I did not handle the federal cases, but Kenny and I stayed in regular contact, and agents kept me broadly informed about how central he had become. I continued to help keep Kenny on track and in the right frame of mind.

Soon, the Justice Department had cases against virtually every senior El Rukn leader. The entire organization — its financial fronts, its leadership hierarchy, and its connections to the Chicago mob — came apart. In the end, when Jeff Fort’s Libyan conspiracy came to light, hundreds of members were arrested. The gang that had terrorized the South Side for two decades was finished.

I can say without exaggeration: it never would have happened without Kenny Morrow. Despite impossible odds, he became the key witness who helped bring down an empire built on crime.

When the criminal trials concluded, Kenny entered into the witness protection program. For a while, I’d get a message through a friend who still had contact with the former Strike Force members—a forwarded hello, a brief update, nothing more. Then, years later, word came back. Kenny had died in Arizona—no foul play, no hit, just the heat. One Friday night, after an argument with his girlfriend, he went drinking. When the bar closed, he was afraid to return home, so he crawled into a metal Quonset hut at a construction site and passed out. By mid-morning the next day, the desert sun had turned that hut into an oven. Still passed out from the night before, Kenny never woke up. They found him curled on the floor when the crew came back to work on Monday morning. Cause of death: hyperthermia.

It was a lonely, sad end to a life full of violence. Yet I’ve often thought that somewhere along that road, Kenny found what he had been seeking. I know that, in addition to reconciliation with his parents, he wanted to be right with God. He wanted to make right what he had done wrong. He became reconciled to his parents. I hope he became reconciled with God as well.

I think of him whenever I read Romans 8:28 — “We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love Him, who are called according to His purpose.” I do not doubt that Kenny was called according to God’s purpose.

I do not know whether he was saved, but I know that God used him — a flawed man with blood on his hands — to bring justice, protect others, and show that even in the darkest story, redemption is possible.

Kenny rose to become a man of great courage. Believe me, spying on the likes of the El Rukn leaders for years, meeting secretly with other government agents and me, at constant risk of being spotted in the wrong place at the wrong time, or of slipping up by saying the wrong thing, losing your poise, or acting out of character, is dangerous work. Some of those men would kill people based only on a suspicion. Anyone who’s done undercover work, even for a few hours, with incredibly dangerous criminals knows exactly the courage it took.

Courage is the one virtue on which every other virtue depends. If even one out of ten churchgoing Christians today had half of Kenny’s courage, we’d live in a different country. We’d be back to the time when you could leave your door unlocked, leave your car running while you stepped into the store, and when faith didn’t just fill pews but changed neighborhoods.

Kenny’s life was a tragedy, but it was also proof that courage can transform it. God took every broken piece of that man’s story and used it to tear down an empire of evil. That is redemption, at least for his earthly life. I hope that his soul was truly redeemed as well.