Megan’s story should awaken every parent to the harsh reality we face. Now, at 17, Megan shares what no child should have to experience. Her journey began as an innocent kindergartner who loved reading, progressed to an adolescent battling addiction to explicit romance novels and other pornography, and continued to her involvement with online predators.

It led to her feeling suicidal and ended with her in juvenile detention.

Her story is a clear indictment of our public institutions, which are failing our children and failed her. You can watch Megan tell her own story here.

Megan didn’t choose this path. She was guided into it by the very institutions we trust with our children’s development and safety. She describes how she was first introduced to explicit sexual material. Initially, it was through online platforms and then through the approval, recommendations, and encouragement from school librarians and teachers.

She started with innocent romance fiction, but it quickly evolved into more sexually explicit content. The material created a dopamine-driven addiction to pornography that left her isolated, experiencing self-hatred, and exposed her to dangerous online relationships with predators.

Her brain had become hardwired with images and descriptions she cannot unsee.

Most striking is Megan’s insight into how lasting this damage is. She stresses that words and images in explicit books form strong, permanent neural connections that can’t be easily erased.

“You can’t unsee those words,” she tells us.

Megan is a teenager whose childhood was taken from her by exposure to material that institutions made easily accessible.

Her mother’s testimony emphasizes what should be evident to any responsible adult. The harm is genuine. The repercussions are severe. And the institutional betrayal worsens the tragedy. You can hear her perspective here.

As a child, Megan’s mother was victimized by a predator who used pornography to make abuse seem normal, leaving lifelong scars. Now, as an adult, she had to watch helplessly as her daughter went through similar suffering caused by obscene books handed out by school librarians.

She describes feeling torn between gratitude for her daughter’s love of reading and horror at discovering what those books contained. She remembers her daughter’s secrecy about what she was reading, hiding the books from her. She felt deep pain for her daughter as she saw Megan experience the shame that often comes with a young person’s natural sense that what they are doing is wrong.

The mother emphasizes an important point that deserves our full attention: librarians are not qualified to decide what children should be allowed to read. Yet, they have portrayed themselves as advocates and supporters who believe they are helping young people by providing access to sexually explicit material.

Not a single competent therapist or counselor would ever recommend that a teen read books depicting sexual assault, incest, or graphic sexual behavior as part of their emotional development. Professional mental health providers understand something that librarians often do not—exposure to traumatic sexual content retraumatizes rather than heals. Loving parents know this too.

Yet, many librarians, teachers, and administrators believe they know better.

Megan’s ordeal didn’t happen by chance. It stems directly from a deliberate ideological stance promoted by the American Library Association and adopted by librarians nationwide. The ALA has made “intellectual freedom” a key principle—meaning offering unlimited access to all materials regardless of age, maturity, or developmental stage.

According to the ALA’s clear policy, librarians see themselves as guardians of access to information. They recognize no requirement to determine the age appropriateness of any book or other material. The organization strongly opposes restrictions, considering any attempt to limit a minor’s access to sexually explicit material as censorship that threatens First Amendment rights.

The ALA states that “only parents or guardians should limit their own children’s access to library materials and services” and that libraries cannot act “in loco parentis” (in place of parents). This approach is so ingrained in library culture that suggesting age-appropriate restrictions often leads to defensive resistance and accusations of censorship.

Since 1982, the ALA has promoted “Banned Books Week“—an annual public relations campaign held every October aimed at attacking and marginalizing parents and community members who challenge inappropriate books in libraries. The campaign depicts concerned parents—often dismissed as “church ladies” or moral busybodies—as enemies of freedom engaged in censorship.

The 2025 theme, “Censorship Is So 1984. Read for Your Rights,” exemplifies the propaganda approach: equating parents who oppose sexually explicit material in children’s libraries with totalitarian government censorship.

The ALA claims that “pressure groups” initiated 72% of demands to “censor” books in 2024. What they call “pressure groups” are often simply organized parents exercising their constitutional right to direct the education of their children. The ALA’s own statistics show that the most common reasons for challenges include “false claims of illegal obscenity for minors” and “inclusion of LGBTQIA+ characters or themes.”

Here’s something I haven’t seen addressed in any of the countless articles published each year during Banned Books Week, or in any coverage of so-called “book banning” controversies: the ALA’s legal justification for unrestricted access to sexually explicit material by minors is based on a fundamental misrepresentation of Supreme Court precedent.

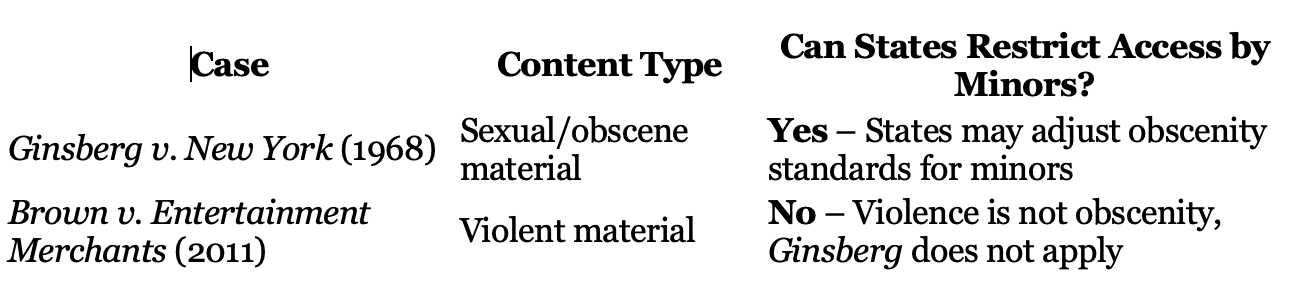

The ALA cites Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2011) to support its claim that minors have First Amendment rights to access information and that “constitutionally protected speech cannot be suppressed solely to protect minors from ideas or images lawmakers deem unsuitable.” On the surface, this argument seems convincing. However, it is a deliberate misapplication of the decision.

Brown specifically addressed violent content in video games, not sexual content. Justice Antonin Scalia’s majority opinion explicitly differentiated Brown from Ginsberg v. New York, stating:

“Because speech about violence is not obscene, it is of no consequence that California’s statute mimics the New York statute regulating obscenity-for-minors that we upheld in Ginsberg v. New York.”

In other words, the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown confirmed that Ginsberg remains good law for sexually explicit material. Scalia pointed out that Ginsberg “approved a prohibition on the sale to minors of sexual material that would be obscene from the perspective of a child“ and that this was constitutionally permissible.

The Brown decision states that violent content cannot be restricted because it is not considered obscenity. Still, sexual content can be restricted under Ginsberg because it is considered obscenity when it involves minors.

The ALA has taken a principle from Brown (that violent content cannot be restricted for minors) and inappropriately applies it to argue that sexual content also cannot be restricted—even though the Brown decision itself explicitly says the opposite.

Ginsberg v. New York (1968) established that “material that is not obscene may nonetheless be harmful for children, and its marketing may be regulated.” The U.S. Supreme Court held that

“it is not constitutionally impermissible for New York…to accord minors under 17 years of age a more restricted right than that assured to adults to judge and determine for themselves what sex material they may read and see.”

The Court explicitly stated that

“the power of the state to control the conduct of children reaches beyond the scope of its authority over adults.”

This directly contradicts the ALA’s assertion of equal access for minors. The actual legal framework is clear:

The ALA acknowledges Ginsberg but now interprets it narrowly, arguing it applies only to “commercial contexts (like selling magazines)” and not to libraries. This is a policy preference masquerading as legal analysis. There is nothing in Ginsberg that exempts educational institutions from the principle that states may protect minors from sexually explicit material. The ALA’s position is not constitutionally grounded—it is an ideological choice that contradicts rather than follows Supreme Court precedent.

The truth is that the ALA has maintained this position that children have the right to access all library books for over 50 years. The ALA added “age” to the Library Bill of Rights in 1967—long before Brown was decided in 2011. The policy document “Free Access to Libraries for Minors” was adopted in 1972 and amended in 1981, 1991, and 2004—all before Brown.

Their pre-Brown legal justifications cited:

1.) Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville (1975): The ALA cited this case in footnotes to their “Free Access to Libraries for Minors” interpretation, specifically quoting: “Speech that is neither obscene as to youths nor subject to some other legitimate proscription cannot be suppressed solely to protect the young from ideas or images that a legislative body thinks unsuitable for them.”

2.) Tinker v. Des Moines (1969): The ALA relied heavily on Tinker, which established that students “retained their First Amendment rights while at school.” The ALA used this to argue that minors have First Amendment rights in libraries as well.

It is clear that keeping all books accessible to children is what they wanted, so they went out and found reasons to support their position. (Curiously, the ALA used the Erznoznik decision as justification for their policy in 1981, 1991, and 2004, even though the ALA specifically acknowledges Ginsberg is valid law and that it specifically allows restricting material for youth. Their own citation undermined their policy position.)

Illinois and many other states have deliberately chosen to protect this ideology by law. They have created specific exemptions from state obscenity laws that would typically restrict the distribution of obscene material to minors. Illinois law includes language that safeguards libraries and schools—exempting them from prosecution under standards that apply to other businesses or individuals.

This legal shield is specifically designed to protect librarians and teachers who distribute material that qualifies as obscenity under the Ginsberg standard.

Many books in school and public libraries likely meet this definition based on Ginsberg’s three-part test: whether the material appeals to minors’ prurient interests, whether it depicts sexual conduct in a clearly offensive way (according to community standards for appropriate content for minors), and whether it lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value for minors.

The existence of these statutory exemptions reveals everything we need to understand. Teachers’ unions, school administrators, and state legislators know that some of what is provided to children is obscene.

Why else would they require legal protection from prosecution? The exemption itself admits guilt—acknowledging that, without statutory protection, distributing this material could expose teachers and librarians to criminal charges.

Federal statutes also remain available as a potential legal tool. Section 1470 of Title 18, United States Code, makes it a federal crime to knowingly transfer obscene material to someone under 16 years old—in other words, up through a student’s sophomore year in high school—using the mail or any facility or means of interstate or foreign commerce. This would almost certainly apply to online books—the very medium through which Megan accessed much of the material that harmed her.

The penalty is severe: a fine and up to 10 years’ imprisonment.

While I am unaware of federal laws being used to prosecute librarians or teachers for providing explicit books to children, the legal authority is there if the political will were ever to be mobilized to apply it.

The problem is that even if state and federal governments suddenly started prosecuting librarians and teachers under obscenity laws or Ginsberg standards, it wouldn’t solve what we’re facing. Such prosecutions would be uncommon, slow to progress through the courts, and likely target only the most obvious cases. Bureaucratic and political will move slowly. By the time a prosecution concluded, many children would have been exposed to harmful material.

The solution sits squarely on the shoulders of parents. Our responsibility as parents is to understand that we cannot rely on the government to protect our children. We must do it ourselves.

Some people might suggest alternatives, such as sending children to Christian schools or homeschooling entirely. These options are available and may be suitable for some families. However, let’s be honest—these options are not practical for most American parents. The majority rely on public schools, and many face financial constraints, work commitments, and other circumstances that make private schools or homeschooling unfeasible.

Public schools will remain the educational foundation for most American children.

The legal landscape changed significantly in June 2025 when the United States Supreme Court issued its decision in Mahmoud v. Taylor. By a 6-3 vote, the Court ruled that public schools must accommodate parents who have religious objections to instructional materials that conflict with their faith. More importantly for our purposes, the Court established that schools have an affirmative duty to notify parents in advance when potentially offensive materials will be used and to allow parents to opt their children out of that instruction.

Justice Alito’s majority opinion made clear that

“the Board should be ordered to notify the parents in advance whenever one of the books in question or any other similar book is to be used in any way and to allow them to have their children excused from that instruction.”

The ruling established that denying parents notice and the ability to opt out “substantially interferes with the religious development of their children.”

This ruling has immediate implications that extend far beyond the LGBTQ+-themed storybooks at issue in the Maryland case. The principle applies broadly: when public schools include instructional materials on topics that could undermine parents’ religious beliefs, they must accommodate families with sincere religious objections by offering and respecting an opt-out right.

The sexually explicit books in school and public libraries—the very material that harmed Megan—qualify. The same applies to much of the material used in nearly every classroom. Teachers use some of these books for instruction and assignments. They have also been exempt from obscenity laws in Illinois and most states. Library books, due to the controversy surrounding them, are known to offend some parents. Under Mahmoud, schools are now required to notify parents in advance about this material so they can protect their children from it.

The hard truth is this: parents must watch the schools and libraries like hawks. We cannot assume good intentions. We cannot trust that adults working within these systems share our commitment to protecting children’s innocence and development in the same way we do as parents.

The evidence, documented in Megan’s story and her mother’s testimony, shows that good intentions do not prevent harm. Even well-meaning librarians, acting according to their professional ideology, can and do place harmful material in children’s hands.

But what actions can parents realistically take?

First, know what your children are reading. This requires vigilance. Ask your children about their books. Look at what they’re checking out. Pay attention to what they bring home. Please don’t assume that because a book is in a school library, it has been carefully vetted for age-appropriateness. The ideology behind library acquisitions isn’t intended to accomplish that purpose.

Second, control access by managing devices. Your child might have her own phone. But you have both the authority and the duty to oversee what that child can do on it. Yes, the digital age makes this complicated. But a parent’s duty to protect hasn’t changed with technology; it’s just more demanding and urgent. Set parental controls. Keep track of usage. Know which apps your child is using—on her phone, tablet, and laptop—and what content she’s viewing. This isn’t an invasion of privacy; it’s the exercise of legitimate parental authority.

Third, know what books are in your child’s school and library. This isn’t as hard as it might seem. Almost every school library across the country can be accessed through a single portal: Follett Software. You can search this database to see which titles are available in your child’s school library. While you won’t be able to review every book, you can identify titles that might be problematic.

Fourth, use the work of watchdogs, who have already done much of this for you. Organizations like RatedBooks.org maintain detailed summaries of books found in school and public libraries. They identify inappropriate sections, detail the sexual or disturbing content, and provide ratings. These resources are invaluable.

Before your child checks out a book, you can search it on Ratedbooks and understand exactly what content it contains. This is not about preventing your child from reading; it’s about making informed decisions about age-appropriate reading material based on accurate information on the content.

Fifth, when you identify a problem, act on it. Notify the school board. Inform the librarian. Please don’t assume they already know the content of every book in their collection. They often don’t. Put your concerns in writing. Be specific. Reference the exact pages and passages that concern you. Document your complaint. This creates a record and demonstrates that concerns have been raised about particular titles.

Sixth, invoke your rights under Mahmoud v. Taylor. Schools must now provide notice when they plan to use materials that may conflict with your religious beliefs and allow you to opt your child out. Exercise this right. Request curriculum information. Ask to be notified in advance. Document your requests and the school’s responses.

If schools fail to comply, they are violating a constitutional right that the U.S. Supreme Court has now clearly articulated. Follow up on non-compliance with a complaint to the Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. File your complaint HERE.

This is not censorship. You are not demanding that offensive books be removed from the library entirely. You are asserting the right to protect your own child’s access to material you deem inappropriate. You are holding institutions accountable for what they place in children’s hands. You are exercising the parental authority that precedes and supersedes any institutional ideology.

What you do or don’t do will make life-changing differences for your child.

The good news in Megan’s case is that she is recovering. She stopped reading sexually explicit material. She is experiencing improved mental health and behavior, and now speaks out on behalf of others caught in similar struggles. Her recovery was not inevitable—it required intervention, support, and the presence of a parent who refused to throw in the towel. Not every child has that advantage.

The path forward is not complicated, but it is demanding. It requires parents to reject the idea that institutions will protect children. It requires us to become informed about what our children are accessing. It requires us to take action when we discover problems. It requires us to speak up and hold librarians, teachers, and school boards accountable for the material they make available to minors.

Megan’s story is a call to action. Every parent who hears her account should ask themselves: What is in my child’s school library? What are they reading? And most importantly: Am I doing everything I can to protect them? The answer to that last question should drive us to vigilance, to research, and to action.

Our children’s development and safety, our children’s innocence, depend on it.